Bánh Chưng: A Rice Cake Wrapped in Love, Labor, and Memory

How Bánh Chưng Became My Family’s Sacred Glue

This year, I had the rare chance to return to my hometown and finally learn how to make bánh chưng, our beloved Lunar New Year rice cake, from my mother’s time-honed recipe. For as long as I can remember, this square shaped bundle of sticky rice, pork belly, mung beans, and leafy green wrapping has been the star of our Tết table rich with history, flavor, and quiet emotion.

But bánh chưng isn’t just food. It’s a tradition one that begins days before New Year’s Eve, as our family prepares each ingredient with care and memory. Every year, my mother leads the process, selecting the best grains of glutinous rice, washing the leaves, and seasoning the pork with the precision of someone who could do it in her sleep (but never would she’s far too meticulous for that).

As children, we helped where we could rinsing rice, cleaning leaves, prepping string while our parents took charge of the wrapping and the long, slow cooking. We’d make dozens, sometimes close to a hundred cakes, to share with friends, relatives, and neighbors. Each one was a little square of love and labor, wrapped tight and given freely.

After we moved to the U.S., we adapted. La dong leaves were swapped for banana leaves, outdoor fires replaced by pressure cookers. My father even built a wooden mold to help us keep the cakes perfectly square. It wasn’t entirely traditional but it worked. And through all the adjustments, the flavor and the meaning stayed beautifully intact.

Now, years later, I’m learning the craft for myself. Guided by my mother’s hands and memories, I’m finally starting to understand why this dish matters so deeply. It’s not just about what’s inside the cake. It’s about who makes it. Who wraps it. Who stays up late tending the fire. And who taught you how.

So today, I’m sharing our family’s bánh chưng recipe not just for the sake of tradition, but to pass along a piece of everything it means to us. I hope it brings your kitchen the same warmth, connection, and yes, a little emotional damage it always brings mine.

Rice Cakes

The Recipe:

Yield:

Make 4 rice 5X5 inch squares

Supplies:

Cutting board

Banana leaves/ la dong

Wooden mold/stainless steel for wrapping

scale

Pressure cooker

String to tight /bamboo string

Foil to wrap the rice cake

Bowl mixer

Drainer basket

pot/ sauce pan

Rice Cake Recipe:

.

🧾 Ingredients for Bánh Chưng (Vietnamese Sticky Rice Cake)

Yields about 5–6 square cakes, depending on size

Sticky Rice Layer:

1 kg sweet glutinous rice (white variety)

1 pack frozen pandan leaves (defrosted, pureed, and strained) – for soaking rice to add subtle flavor and light green color (optional)

2 tbsp salt

📝 Tip: Soak the rice overnight in water (or pandan water) for better texture and color absorption. Rinse and drain before assembling.

Mung Bean Filling:

1 package split mung beans (approx. 400g–500g)

1/2 cup neutral oil (canola or vegetable)

2 tsp sea salt

📝 Soak mung beans for at least 4–6 hours or overnight. Steam or boil until soft, then mash and season. Some families lightly sauté it in oil for added richness.

Meat Filling:

1 kg pork belly (cut into thick slices or chunks)

4 tbsp crushed or ground black pepper

1 tbsp sea salt

1 tsp sugar

Optional:

1–2 tsp fish sauce (for deeper umami)

1–2 shallots (finely chopped)

A pinch of MSG if you want to taste your ancestors

📝 Marinate the pork for at least an hour (overnight is better) to let the flavors develop. Pork belly is preferred for its layered fat and flavor.

See my videos instruction how to wrap the rice cake here : https://youtube.com/shorts/A9_CrgGcEFk

How to Wrap & Cook Bánh Chưng Using a Wooden Mold

Prepare the Wrapping Station:

Cut banana leaves to size based on your wooden mold. Wash them thoroughly and wipe dry. You can briefly steam or blanch them to make them more pliable.

Place 4 overlapping pieces of banana leaf inside the mold in a cross pattern, shiny side down. This creates a strong base to hold the filling without tearing.

Set the mold on a flat surface, leaf-lined and ready to fill.

Assemble the Bánh Chưng Layers:

Start with a layer of soaked sticky rice at the bottom of the mold.

Add a layer of cooked mung bean paste, pressing it gently to flatten.

Place a chunk or slice of marinated pork belly in the center.

Add another layer of mung bean, followed by a final layer of sticky rice to cover the filling completely.

Gently press everything down—firm and compact is key. Use your hand or a pressing board to ensure there are no gaps.

Wrap and Secure the Cake:

Fold the banana leaves tightly over the top to close the package.

Use string (day lạt or cooking twine) to tie the cake securely in a crisscross pattern. The goal is to keep the filling tightly packed and prevent it from leaking during cooking.

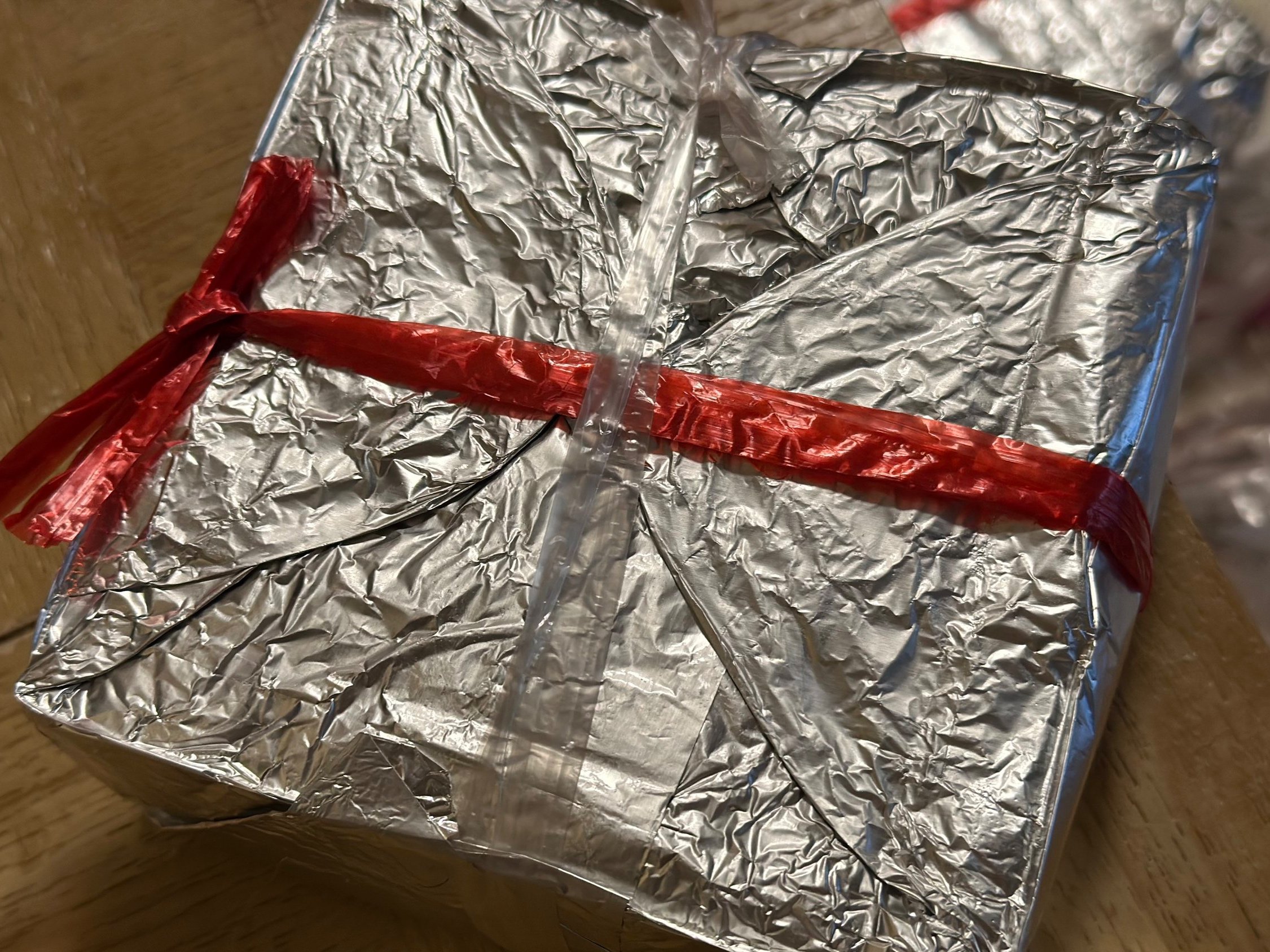

Optional pro tip: Wrap the outside in foil to reinforce the shape and prevent leaks if your banana leaves aren’t perfect.

Press the rice down evenly inside the mold

Boil the Bánh Chưng:

Line the bottom of a large stockpot with extra banana leaves to prevent scorching.

Gently lower the wrapped cakes into the pot and fill with water until they’re fully submerged.

Bring to a full boil, then reduce to a gentle simmer.

Cook for 8 hours, making sure to constantly top up the pot with hot water as needed to keep the cakes submerged.

Drain and Press (This Part Matters):

Once the cakes are done cooking, remove them carefully using tongs.

Place them on a tray and set a flat board or tray on top with a heavy weight (books, another pot, etc.). This helps press out excess water and gives the cakes a firm, dense texture.

Let them press for several hours or until fully cooled.

Finishing Touches:

Once cooled, remove the foil and inspect your masterpiece. Rewrap in decorative plastic wrap or banana leavesfor presentation, if desired.

Store at room temperature for a few days or refrigerate for longer shelf life. To reheat, steam or pan-fry slices for crispy edges.

The final bánh chưng should be dense, slightly gooey, and deeply aromatic—with every bite carrying that rich blend of sticky rice, creamy mung bean, and savory pork.

Use instant pot for small rice cake

Congratulations, you’ve successfully made a food that could emotionally cripple someone with its nostalgia.